Publications & reports

Participatory Action Research (PAR): A Tool for Transforming Conflict

A case study from south central Somalia

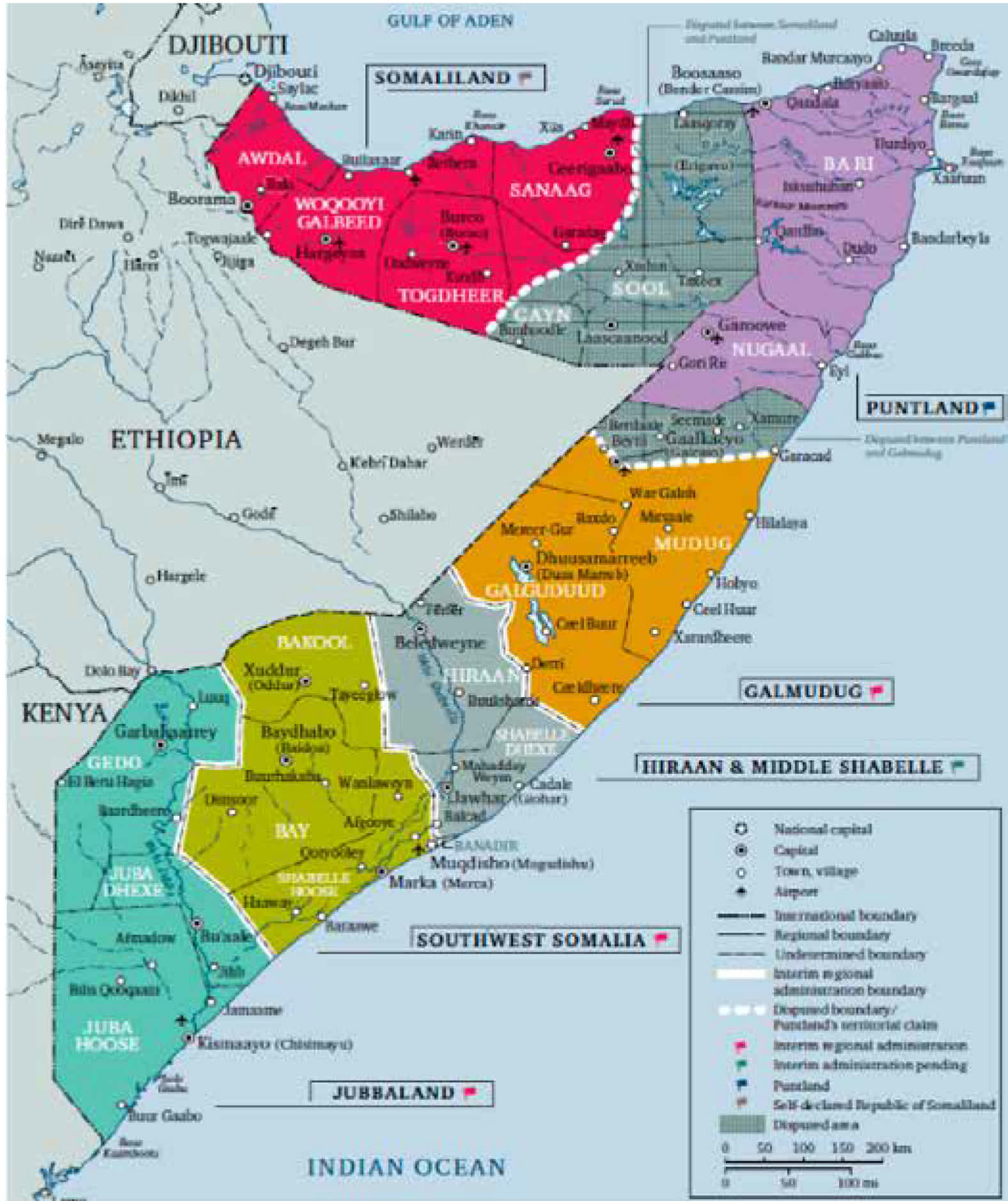

This latest publication, “Participatory Action Research (PAR), a tool for transforming conflict—a case study from south central Somalia”, documents the key challenges and opportunities for implementing PAR in the Somali context. It is based on the first phase of a three-year peace process within and between communities in Galgadud, Hiran and Middle Shabelle, facilitated by the Life & Peace Institute in partnership with the Zamzam Foundation.

- Date

- Type

- Report

- Country/Region

- Somalia

Summary

“The communities are used to being told what to do and how to resolve their issues. On the contrary, in the PAR process, we ask them to tell us what they think their problem is and what their solution might be. They [the communities] are the driving force and know the solution.” – Zamzam Foundation staff, male, 27 August, 2015

This publication outlines the key processes, as well as challenges and opportunities, with implementing Participatory Action Research (PAR) in the Somali context – expanding upon the Life & Peace Institute’s (LPI) own internal research and scholarship on implementing PAR in different conflict contexts. The report

engages with current research on applying PAR to local peacebuilding efforts,

and offers new insights from original participant and staff interviews, and findings

of a summative evaluation of the first phase of LPI’s Conflict Transformation

and Inter-Clan Joint Resource Management (or CRM) project (implemented from

March 2012 to September 2015) in central Somalia.

The report, thus, aims to examine the processes of negotiation and adaptation

of applying the PAR methodology to the specific context of peacebuilding

programming across south central Somalia, to explore whether PAR programming

(as a methodological approach to dialogue and peacebuilding discourse)

has proven effective and contributed towards de-escalating local tensions (around

certain issues and in certain contexts), and if so, how it could be further adapted

and standardised (across programmes and disciplines).

To date, top-down institutional approaches to peacebuilding attempted by a

range of government and non-government actors have proven largely unsuccessful.

As such, the aim of this report is to examine the new neo-liberal push, by

international actors and domestic governments, for local agency and traditional

and hybrid governance structure, as the solution for positive societal change and

a way for building bridges for national and federal peacebuilding and national

dialogue processes. Thus, this report hopes to examine the applicability and

relevance of the PAR approach to local peacebuilding in the context of deeplydivided

communities, to ensure that PAR programming (ensconced in this new

development framework and its focus on local decision-making and agency) is

demonstrating positive effects on the levels of tensions and violence, is strongly

supported by the community, and is in line with values and conditions deemed

necessary by the community for longer-lasting peace (and doing “no harm”).

It is also hoped that this report will contribute to standardising the institutional

practice of PAR more broadly. Examining the impact of peacebuilding projects

is notoriously difficult, and the inherently open and flexible approach of PAR

programming makes this no easier. Yet, findings indicate that clear guidelines

and risk mitigation measures, as well as systematisation of dialogue procedures,

have served to standardise both programme responses and ensured a degree of

continuity in project implementation and outcome in the Somali context that

has enhanced local reception of PAR programming, as well as eased the task of

analysing and deciphering cross-cutting trends. LPI certainly encountered key

challenges applying the PAR approach to the local Somalia context, and in attempting

conflict transformation in ways that fundamentally deviate from traditional clan-based systems of conflict resolution, namely the prominence of elders in decision-making and the focus on quick-impact resolution.

Yet, findings indicate that participants were receptive to key elements (the focus

on incremental and longer-term dialogue processes, the unique staggered approach

to intra- and inter-clan conflict, and the focus on peace agreements). The

wider inclusion of women and young people still remains a significant challenge,

although significant strides were made (with all intra-clan dialogues comprising

at least 15 per cent women).The findings show that despite initial scepticism and

participant concerns about project gains (the lack of immediate tangible benefits

and concerns about more time required for seeing visible change or peace), the

majority of participants interviewed as part of an external evaluation1 (including

elders) indicated high trust in the incremental, sustained and inclusive dialogue

processes.

Community members strongly support PAR programming in the project

areas, noting positive changes in attitudes towards conflict resolution (its mechanisms

and operators). In participant estimations, this was due to 1) strong community

trust in the local implementing partners (trust established on pre-existing

knowledge of the institution, and its commitment, capacity and integrity), and 2)

the observed standardisation as well as flexibility in approach (its strong focus on

incremental sustained dialogue and agreement formation, but also openness to

holding dialogue quickly in the event of crisis situations if called for by the communities).

Participants also noted tangible effects of PAR programming. Following the

first phase of programming, participants who had reported high rates of segregation

between clans and low levels of clan cohesion, noted positive transformations

in the attitudes and behaviours towards intra- and inter-clan conflict (its

value and cost), as well as the strategies toward conflict prevention (preferring

more sustained agreements to resolving underlying issues rather than quick-impact

solutions). Participants reported an increase in informal engagement between

clans in the business and social spheres (indicating transferrable practices

of open dialogue into the informal sphere), as well as a commitment to embracing

nonviolent approaches to conflict (characterised by a willingness to negotiate

and engage in dialogue during periods of high tension before the conflict starts,

as well as promoting nonviolent approaches once conflict had begun, either

through the returning of seized property or the convening of peace committee

discussions).

The decrease in the number of requested crisis interventions in the project areas

since the project inception – especially in the context of increasing local conflicts

and contestation across Somalia since the commencement of state formation

and federalisation agendas – also points to positive programmatic outcomes.

Yet, through a continuous project of risk analysis, validation and feedback systems,

LPI’s approach to PAR will continue to adapt to vastly changing dynamics

on the ground at the local level. National statebuilding processes have certainly

affected local activities, and the ongoing state formation and implementation of

the federal project are generating new forms of conflict in addition to aggravating

old clan rivalries.

Additional challenges for PAR programming more broadly come from fractured

authority structures (lack of community trust in public institutions, regional

administrations or the national ‘state’), and high levels of clan mistrust (resulting

from decades of protracted conflict and the implementation of a new federal

system). The importance here is to ensure that the process remains locally-driven

at every stage, that all stakeholders are involved, but that local conflict communities

take the lead in identifying points of conflicts, convening dialogues, and forming and implementing peace agreements.

1 “Summative Evaluation of CRM Phase 1”, Forcier Consulting, November 2015.