Sustaining Peacebuilding Work in a Crisis:

the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic in Somalia

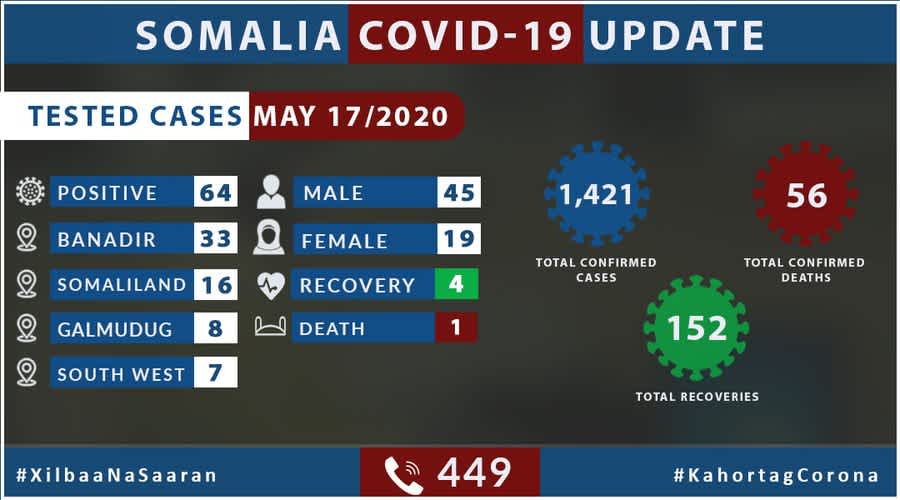

On 16 March 2020, Somalia recorded its first case of COVID-19. According to the World Health Organisation’s (WHO’s) COVID-19 Dashboard – a website tracking global figures of the pandemic – the Horn of Africa nation had over 3000 confirmed cases by early July.[1] It is also stated that Somalia has one of the world’s least-equipped health systems after years of conflict and poverty, leading to fears that untold numbers of cases might be going undetected in the region.[2]

To date no information has been immediately available about any virus cases in al-Shabaab strongholds that remain off-limits for health workers and authorities, or how COVID-19 cases would be confirmed. However, latest reports from media sources controlled by al-Shabaab state that they have set up a hotline contact number in Jilib and have asked the community to report any symptomatic cases. If al-Shabaab also start sharing infection rates, then reports on the virus will be nationwide and not only those areas controlled by the government.

The outbreak of COVID-19 has exacerbated the already existing crises of conflicts, droughts, floods and locust invasion. With weak health and governance systems, poor road networks, the corona virus is not only a health crisis but a humanitarian crisis too. The social nature of the Somali community – which relies on physical gathering to pass information, praying together and enjoying social events jointly – has negatively impacted the restriction measures imposed by the government. Infection numbers are rising despite efforts by the government, the international community and civil society to bring the infections under control.

COVID-19 has also impacted significantly on family incomes. Many families in Somalia depend on remittances from their kin who live abroad. Those relatives in North America and Europe have been hit by the pandemic, with many rendered jobless and unable to remit any money to their families in Somalia.

For peacebuilders, the traditional approaches of convening conflict resolution meetings and gathering communities for sensitization and training can no longer be done, as per the government directives we all now preach isolation, physical distancing and the stay home gospel. Another worry for peacebuilders is that humanitarian and health responses may not be sensitive to already existing social divisions and conflict fault-lines. If crisis responses are not implemented with conflict sensitivity, the urgency of responding to the crisis may widen exclusion and deepen or escalate conflict.

With the government’s measures of restricting movements, domestic crime levels are reported to have increased. From anecdotal sources, cases of rape and gender-based violence are reported to be on the rise.[3] The lack of income as people stay at home and subsequent frustrations is taking its toll on families who are struggling to feed their children. Due to the social stigma attached to the virus, the victims go through enormous trauma and isolation without any counselling support. As a result, it is feared that suicides and anti-social cases such drug abuse may rise if the situation is not contained. Families prefer to hide persons with COVID-19 symptoms at home and so going for voluntary testing is not an option for fear of the consequences like indecent burial of the deceased and further isolation of the family.

As the frequency of domestic violence rises, access to justice continues to dwindle. Formal courts are usually based in urban centers and with current travel restrictions, those in rural areas cannot access it. Added to this, the government has asked non-essential services – meaning those who do not offer services like security, food, and health – to work from home. This has resulted in a reduction in the number of active courts even in urban centers and this denies access to justice particularly for the poor and marginalized groups who are often at increased risk of violation during this period.

Peacebuilders today face an unprecedented challenge during this crisis. Firstly, on how to sustain their work when priorities are increasingly shifting towards emergency humanitarian response. Secondly, on how to change their mode of operations to conform to the restrictions imposed because of COVID-19 as well as emerging conflict situations. Re-strategizing and re-tooling peacebuilding work is inevitable as the pandemic rolls out. Peacebuilders must work closer than ever before with their humanitarian counterparts and governments to reduce the potentially negative impact of emergency interventions on conflict dynamics in order to ensure a cohesive society during and after the crisis period.

Peacebuilders must not only join the chorus of information dissemination about COVID-19 and build trust between the various sectors and the community but must also lead in designing flexible, adaptive and responsive approaches.

Traditional communities in Somalia who have limited access to information have been receiving mixed messages regarding the pandemic. The spread of fake and unsubstantiated information on social and local media has confused the public and led to mistrust of information from sources like the Ministry of Health. Unless communities accept and own the reality of COVID-19, reducing the spread will be an uphill task.

There are significant roles peacebuilders working in fragile and conflict affected environments can play. Below are a set of 10 recommendations for peacebuilders, which is not exhaustive:

1. Peace actors should reorganize and redesign innovative ways of carrying out their activities during the crisis. See point number 7 below too.

2. Work without silos: This calls for peacebuilders and the humanitarian workers to work seamlessly as a team.

3. Emphasize conflict sensitivity at all levels: Peacebuilders need not only cooperate as a joint society of peace actors but must also collaborate closely with other humanitarian and health actors. They should ensure the messages shared and the approaches of all actors are conflict sensitive.

4. Tracking and monitoring of violations: In order to add value to the crisis response, peacebuilders should focus on monitoring human rights violations by both conflict actors and existing government authorities such as law enforcement agencies. Torture, false accusations, unwarranted quarantine and arrests, police brutality, among others, are all common and rising issues reported during this period. Domestic violence also needs to be documented. Keeping tabs on numbers of violations during this period will not only reduce the atrocities but raise consciousness among the actors.

5. No one size fits all model: Every region has its own conflict dynamics but there is a tendency to spread uniform intervention without being sensitive to the local dynamics of relationships and conflicts. It is the duty of peacebuilders to engage all actors to encourage a culture of ownership of the responses and reduce exclusion of sections of the community traditionally left out of decision-making processes.

6. Trust and relationship building: Building trust between the community and actors in the crisis is very important to successful treatment and prevention of the corona virus. Countries have adopted a militaristic approach to containing COVID-19 and this has increased resistance from the community and led to mistrust of information given by the state about the pandemic. Peacebuilders, using their networks at all levels, should lead in bridging the relations between actors and especially with the state by engaging in dialogue and messaging in a responsive way.

7. Adaptability and flexible responses: Peacebuilders need to be flexible and adopt new strategies to reach out to the wider public even as they observe government regulations on staying at home and distancing. Focus should be on building new virtual tools that can be accessed remotely. Investing in technology is key to continuing to operate now and after the crisis particularly in urban centers.

8. Trauma healing and counselling: The legacies of the virus will be long-lasting than any other crisis that the community has faced before as they are not used to this kind of issues that keeps friends and families apart. In preparation for post-crisis issues, peacebuilders should consider trauma healing and counselling as key peacebuilding tools going forward. It is possible that the crisis will reduce the community coping mechanisms by dropping numbers of social events and forums like “Faddi kudirir” (where Somali men converge in coffee houses to analyze social and political events), and communities will need to explore new mechanisms of processing stress and trauma as well as build up social cohesion and resilience.

9. Joint advocacy: It is feared that donors and governments will overlook peacebuilding as the humanitarian and health crisis increases. This would not only reduce the funding available to peacebuilders but also erode the gains made and potentially exacerbate the already fragile peace that has been gained in some spaces. Peacebuilding efforts are equally important during and after this crisis and efforts should be made to share this message, as a community, with donors and governments.

10. Act with speed: Timely response is of the essence during crisis for humanitarian actors as well as peace actors. Authority and decision-making powers should be devolved to the local level as much as possible to make faster response possible.

[1] https://covid19.who.int

[2]https://covid19.who.int

[3] https://www.saferworld.org.uk/resources/news-and-analysis/post/884-gender-and-covid-19-responding-to-violence-against-women-and-children-in-somalia

Most recent blog posts

2026-01-13

Placing Local Voices at the Centre of Regional Peacekeeping ConversationsA Reflection from the Horn Dialogue Series IV